[ad_1]

Call it learning loss or unfinished learning or a learning gap or a learning opportunity. When Janira Martinez looks back at the 2020-21 school year, all the screen time blurs together.

Joining live Zoom classes; completing asynchronous assignments; chatting with classmates on school software. Or, perhaps, browsing social media or catching up on Netflix when she should have been doing one of those other things.

“I was more susceptible to discover the many wonders of the internet or simply binge a show for hours,” the 10th grader at Peekskill High School in Westchester County said. “Everyone may joke about it, but they’re also semi-serious when they say they didn’t retain any information taught or believe the information was taught in the first place.”

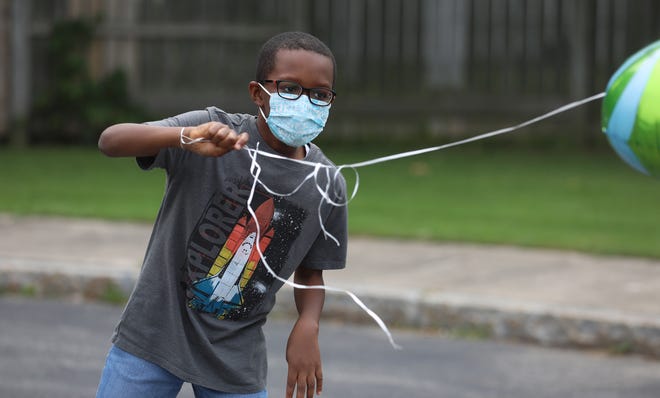

As New York students return en masse to physical classrooms this fall, one of educators’ key tasks will be assessing their academic status compared to where they ought to be — though “ought to be” is a contentious premise on its own — and adapting their curriculum and pedagogy to the effects of the last 18 months under COVID-19.

Not all students have been affected in the same way. Some, well equipped for online learning and richly supplemented with extracurricular activities, zipped ahead while school was disrupted. Others have stagnated or dropped out altogether, exacerbating an already wide academic gap predicated on race, class and wealth.

You ask, we answer:Have questions about COVID protocols in New York schools?

More on bus driver shortage:Hudson Valley’s schools face driver shortage; 500 Yonkers students may not get a ride

Most teachers push back against the notion that their students have lost anything, though large-scale studies have shown definite declines. But all agree students are returning to school in a unique position — and that schools must rise to the occasion.

“You don’t teach a textbook, you don’t teach a topic; you teach children,” said Nick Bianculli, a math teacher at Blind Brook High School in Westchester County. “So you always have to stop and say: ‘OK, where are the students right now? Where can I take them? And how do I do that?'”

How are learning losses measured?

The fundamental case for the idea of learning loss is clear: every student in New York has missed at least part of their standard educational experience since March 2020. Some have missed nearly all of it.

Two major studies released this summer assessed the damage. One, by the non-profit NWEA, measured standardized test scores to show that students made less academic progress in 2020-21 than they normally would have. The disparity was worst for non-white students and those in high-poverty schools.

Another, by the consulting firm McKinsey and Co., echoed the same findings, showing students had lost on average five months of progress in math and four months in reading. It also showed troubling effects on graduation and college enrollment rates as well as student mental health.

“The fallout from the pandemic threatens to depress this generation’s prospects and constrict their opportunities far into adulthood,” the McKinsey report authors wrote.

The disparities by race and wealth are discouraging but not surprising. High-poverty districts across New York spent a huge amount of energy distributing laptops and internet hot spots to thousands of families without reliable home internet and devices. Many of those families also lacked the space, money and adult presence to ensure a conducive environment for at-home learning.

“Pandemic-related learning loss has been especially damaging to our most vulnerable populations,” Lester Young, chancellor of the state Board of Regents, said at a conference in August.

Stimulus funds may aid response

School leaders have been thinking about how to address that learning loss since the very beginning of the pandemic. As they put their plans into place this summer, they received a significant financial assist.

Between December and March, the federal government passed three major stimulus spending bills. Among their provisions were massive funds for local schools to buffer children from the worst of the pandemic in the classroom.

The Rochester City School District, for instance, saw an infusion of nearly $284 million. Smaller districts got proportionate amounts of money to hire new support staff and teachers and make infrastructure improvements.

That all happened at the same time the state Legislature was boosting its own education funding. The end result was a well-timed burst of outside money for schools across the state.

“The sky’s the limit now,” said Suzanne Pettifer, executive director of curriculum and instruction in the Greece Central School District west of Rochester. “It allowed us to order all the resources and hire all the teachers we needed.”

Much of that extra support began in summer school. At Greece’s West Ridge Elementary School, both the number of summer programs and the number of students served increased dramatically in 2021.

One such student, a third-grader named Brandon, was sitting one day at a small table with reading specialist Ellie Muoio, puzzling over a pile of yellow letter tiles.

Muoio arranged and rearranged them and asked Brandon to sound them out.

T-O-T. H-O-T. H-O-P.

“Why doesn’t that one rhyme?” she asked him.

“It doesn’t have O-T,” Brandon mumbled from under his mask. They then began reading a book: How the Tiger Takes Care of Her Babies.

In East Rochester, Superintendent Jim Haugh said summer programs focused on targeted reading and math skills, plus social-emotional learning.

The returns, he said, were encouraging.

“Once you started to focus in on some of the essential skills, students really rebounded quickly,” he said. “Students are really very resilient; they’ll respond to whatever challenge you put in front of them.”

Accelerating changes at school

Nonetheless, many educators believe the concept of learning loss obscures the true nature of the task at hand.

LaShara Evans, principal of Flower City Community School 54 in Rochester, prefers the term “unfinished learning.”

“Even if students haven’t been in school since March 2020, they learned something,” she said. “Even if they’ve just been home with their family, learning is everywhere.”

Pettifer, from Greece, said she fears the term “learning loss” will lead to viewing students in terms of deficits rather than strengths.

“They really haven’t lost anything; they just haven’t had time to learn (everything) yet,” she said. “What skills do they have and how can we build on that?”

Looking forward

Educators in many New York schools agreed that the first critical step once school reopens is ensuring that students feel safe and ready to learn.

From there, many education leaders, including Chancellor Lester Young, hope that the disruption of COVID-19 will cause a faster transition to a broad rethinking of how schools can serve children better.

“For too many New Yorkers, the old normal is a very unhealthy place, a place where people are traumatized daily by their circumstances and lack of opportunity,” he said.

According to Alprentice McCutchen, a history teacher at New Rochelle High School in Westchester, that includes a reconsideration of the nature of learning itself.

“Is learning just moving at a Mach 5 rate to inundate students with content, content, content?” McCutchen asked. “Or are there opportunities to teach and apply skills? This can spark a conversation about what learning can be and should be.”

Contact staff writer Justin Murphy at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

[ad_2]

Source link